Flow Blocks: Protecting Your Deep Work Time

The Evidence-Based System for Scheduling, Defending, and Optimizing Uninterrupted Focus Time—Transforming Fragmented Days Into Engines of Exceptional Output.

Ultradian Alignment. Don’t fight your biology. Sync your work blocks with your brain’s natural 90-minute energy peaks.

The Hidden Cost of Fragmented Attention

You arrive at work with clear intentions: finish the proposal, solve the technical problem, write the strategic plan. Eight hours later, you leave exhausted—yet somehow, none of those important tasks are complete.

Where did the time go?

The answer is hiding in plain sight: your day was shattered into fragments so small that deep work became impossible.

A typical knowledge worker’s day unfolds something like this: You start on the proposal at 9:15, but at 9:23, a Slack notification pulls you away. You return at 9:31, but at 9:47, someone stops by your desk. At 10:00, you have a “quick” 30-minute meeting. By 10:45, you’re back at the proposal—but now you’ve lost the thread. Where were you? What was the key insight you were developing?

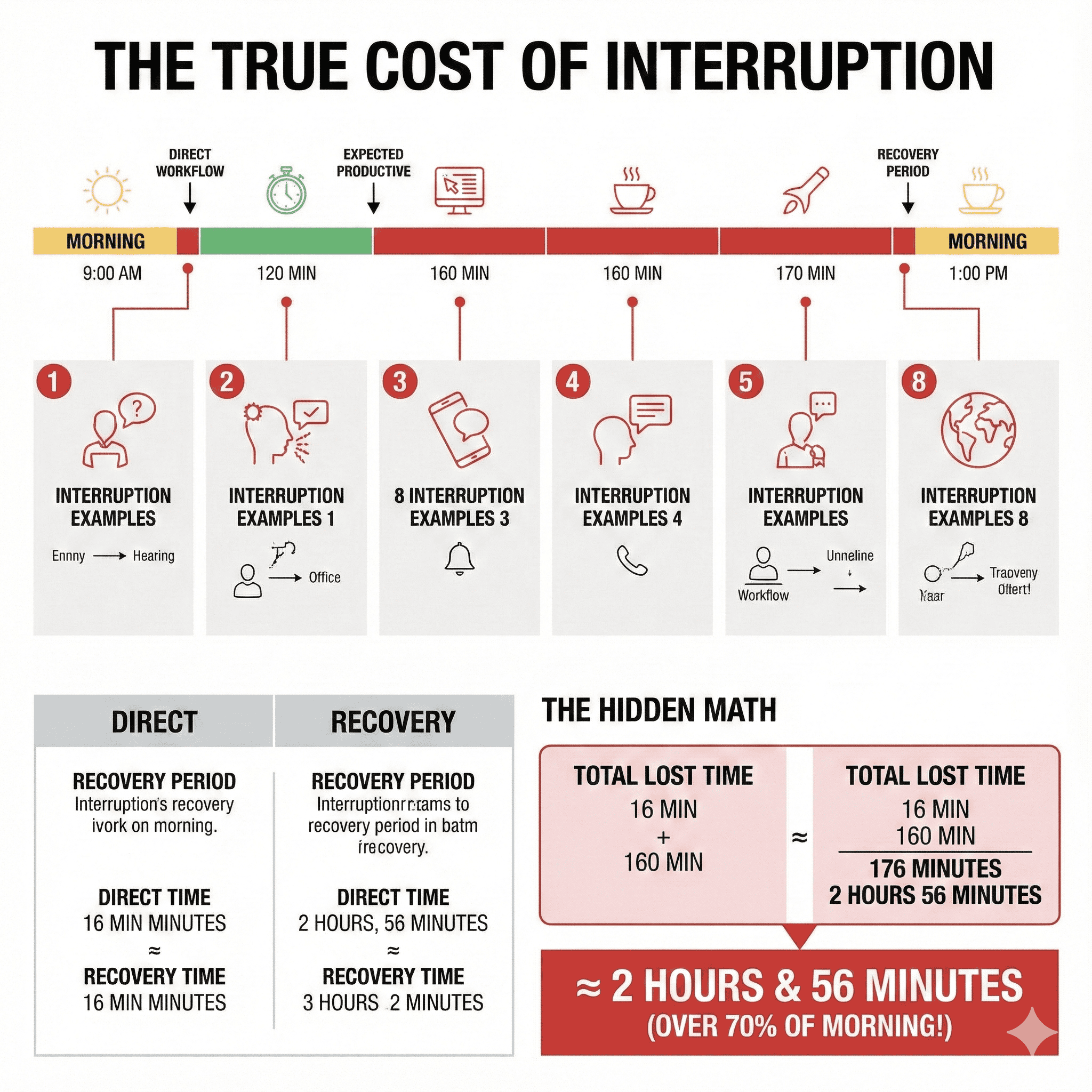

Research on workplace interruptions reveals the devastating mathematics of this pattern. Studies show that the average knowledge worker is interrupted every 3-5 minutes. Each interruption requires an average of 23 minutes and 15 seconds to fully recover focus and return to the original task. If you’re interrupted 8 times in a typical morning, you’ve lost over 3 hours to recovery alone—even if each interruption only took 2 minutes.

But the damage goes deeper than lost time. Research on attention residue demonstrates that even after you’ve switched back to your original task, part of your attention remains on the interrupting task. This residual attention reduces the cognitive resources available for your primary work, degrading both quality and speed.

The result? You work harder and produce less. You’re exhausted by 5pm, but your important work remains unfinished. You start questioning your discipline, your focus, your capability—when the real problem isn’t you at all. The problem is that your schedule is architecturally incompatible with how your brain actually produces high-quality work.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: deep cognitive work requires uninterrupted time. Not “mostly uninterrupted.” Not “interrupted but quick recovery.” Genuinely uninterrupted, protected, defended chunks of time where your brain can fully engage complex problems without the constant vigilance required when interruption is possible.

Elite performers across every field understand this. They don’t “find time” for deep work—they build systems that protect it. They treat focus time as the non-negotiable foundation of their productivity, scheduling everything else around it rather than squeezing deep work into whatever gaps remain.

This guide teaches you to build that system. You’ll learn the biological basis for optimal work block duration, the calendar architecture that protects focus time, the communication protocols that establish boundaries, and the implementation strategies that make it sustainable.

By the end, you’ll have a systematic approach to protecting flow states and deep work that transforms your relationship with time and productivity.

Why Your Brain Needs Uninterrupted Blocks Science

Your brain isn’t a computer that can seamlessly switch between tasks. It’s a biological system with specific requirements for entering and sustaining high-performance states.

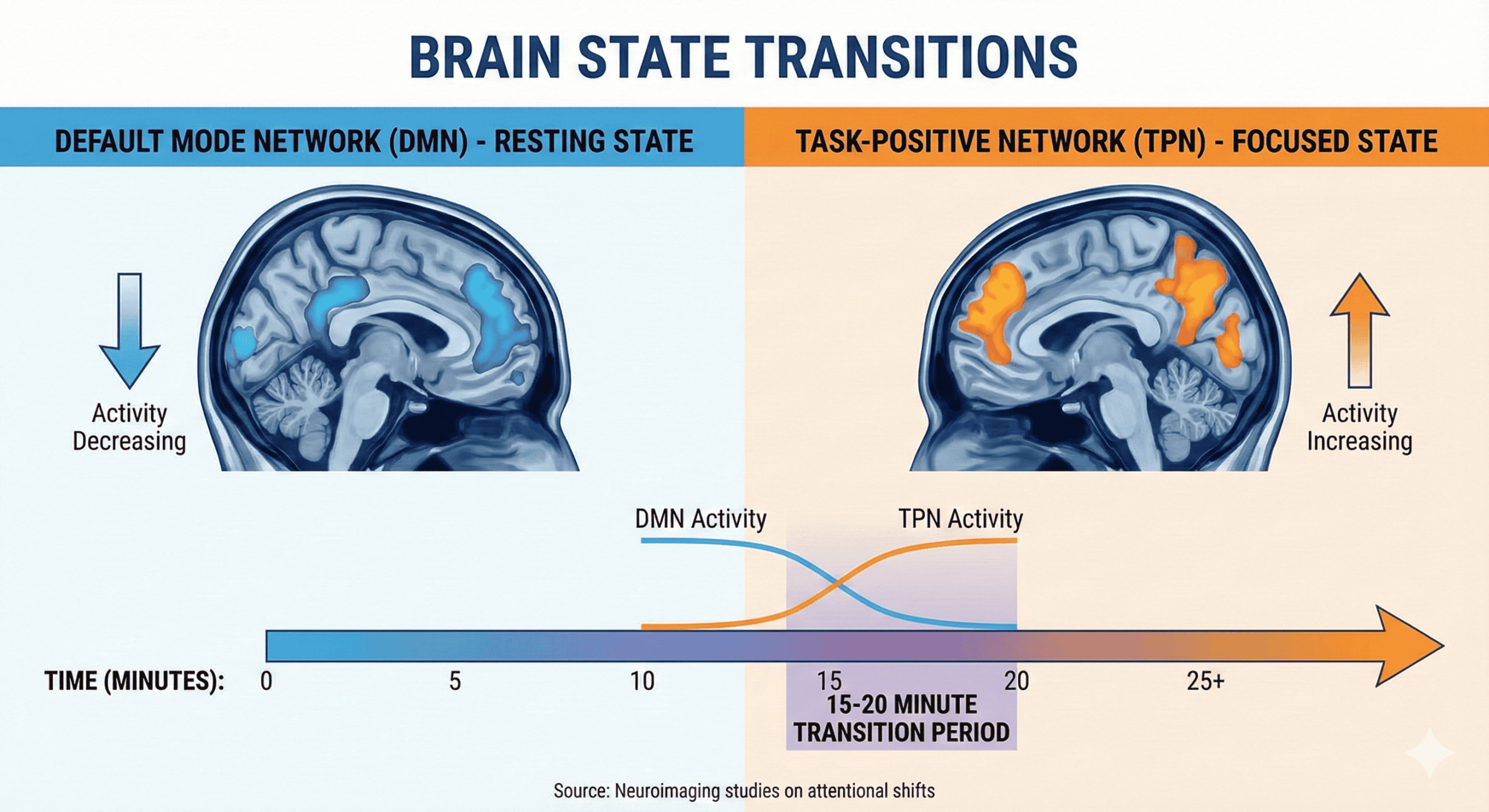

Research using neuroimaging reveals that transitioning from scattered attention to focused concentration involves measurable changes in brain activity patterns. The default mode network—active during mind-wandering and self-referential thought—must deactivate while task-positive networks—responsible for focused attention and goal-directed behavior—activate. This transition takes time and mental resources.

When you attempt to work in fragmented conditions, your brain never fully completes this transition. You operate in a hybrid state: partially focused on work, partially monitoring for interruptions, never achieving the full cognitive engagement that produces exceptional output.

The Attention Residue Problem

Research on attention residue provides perhaps the most compelling evidence for why protected blocks matter.

When you switch from Task A to Task B—even if you complete Task A—part of your attention remains on the previous task. This residue reduces the cognitive resources available for Task B, impairing performance. The effect is even stronger when Task A is incomplete or time-pressured.

In practical terms: when you check email in the middle of writing a report, your cognitive capacity for the report decreases even after you’ve closed your email client. Part of your mind is still processing those messages, wondering how to respond, feeling the pull to check again.

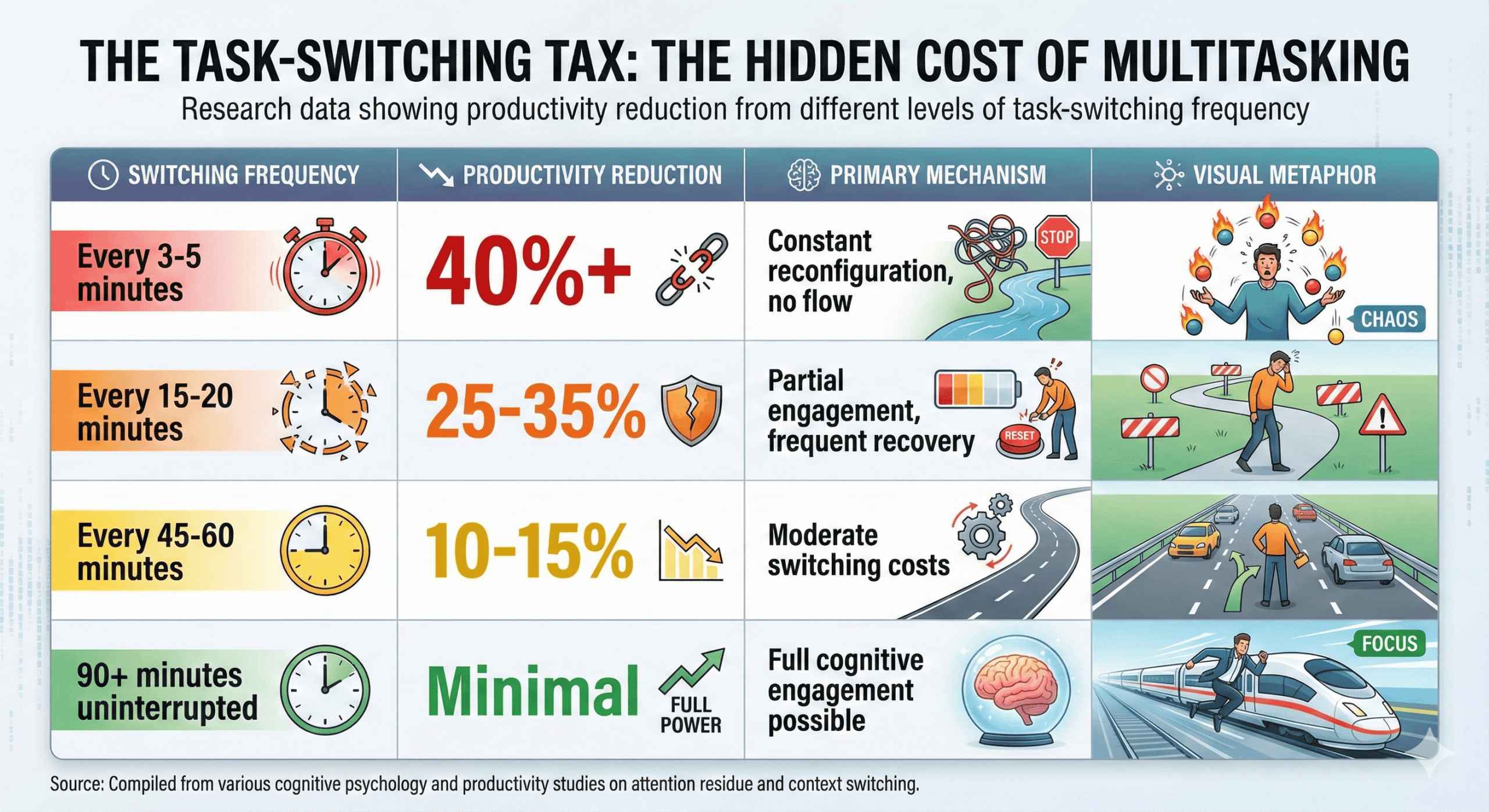

Research demonstrates that people who switch tasks more frequently show reduced depth of processing and lower quality output compared to those who complete single tasks before switching. The conclusion is clear: task-switching has cognitive costs that persist well beyond the moment of interruption.

The Task-Switching Tax

Beyond attention residue, each task switch imposes a direct cognitive cost. Research on task-switching shows that every transition between tasks requires mental reconfiguration—loading new goals, activating relevant knowledge, suppressing irrelevant information.

Studies demonstrate that multitasking can reduce productivity by as much as 40% compared to focused single-tasking. This isn’t because people are bad at switching—it’s because switching inherently requires cognitive resources that then aren’t available for the actual work.

The Incubation Effect

Uninterrupted blocks also enable the “incubation effect”—the phenomenon where complex problems solve themselves through unconscious processing when given sustained attention followed by rest.

Research on creative problem-solving demonstrates that breakthrough insights often emerge after periods of focused engagement followed by disengagement. The brain continues processing problems unconsciously, and solutions surface spontaneously. But this requires adequate initial engagement—the mind must be fully immersed in the problem before incubation can work.

Fragmented attention prevents this full immersion. You never engage deeply enough with problems for unconscious processing to take over. The result: not only do you accomplish less during work hours, but you also lose the between-session cognitive processing that produces creative breakthroughs.

Your brain needs protected blocks for biological reasons, not just organizational ones. Task-switching taxes, attention residue, and blocked incubation aren’t flaws in your focus—they’re features of how brains work. The solution isn’t to focus harder but to structure time so your brain can engage naturally.

Ultradian Rhythms: Your Brain’s Natural Work Cycles Bio-Rhythms

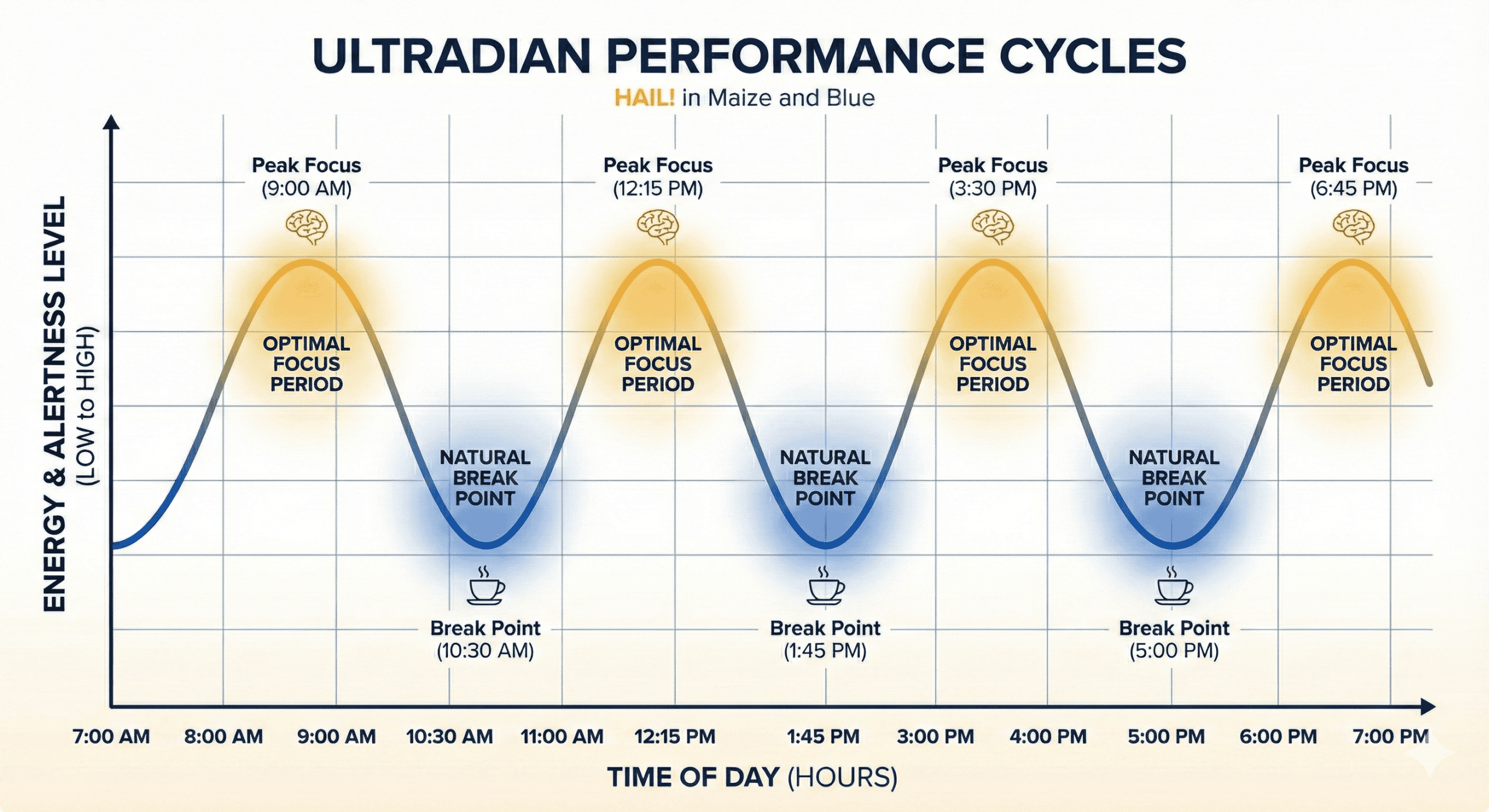

Your body doesn’t operate at a constant energy level throughout the day. Instead, it cycles through roughly 90-120 minute periods of heightened alertness followed by periods of reduced energy—patterns called ultradian rhythms.

Research on these biological rhythms traces back to studies on sleep architecture, which discovered that sleep occurs in approximately 90-minute cycles. Subsequent research demonstrated that similar rhythms continue during waking hours, affecting alertness, cognitive performance, and energy levels.

During the high-energy phase of each ultradian cycle, cognitive performance peaks—attention is sharp, working memory is optimized, and complex problem-solving ability is enhanced. During the low-energy phase, performance naturally dips, and the brain signals a need for rest through subtle cues: restlessness, difficulty concentrating, increased errors.

Research on work patterns among elite performers across domains—musicians, athletes, chess players, writers—reveals a remarkable consistency: they typically work in focused sessions of 60-90 minutes, followed by breaks. Studies of deliberate practice show that even world-class performers rarely sustain truly focused practice for more than 4-5 hours daily, structured in 1-2 hour sessions with recovery periods between.

The Science of 90-Minute Blocks

Why does the 90-minute duration appear so consistently across research and elite practice?

The answer lies in brain metabolism. Sustained focused attention requires glucose and other metabolic resources. Research on cognitive fatigue demonstrates that approximately 90 minutes of intense concentration depletes certain neural resources, after which performance naturally declines regardless of motivation or effort.

Pushing beyond this natural limit doesn’t produce more output—it produces lower quality output at higher subjective cost. Research on extended work sessions shows declining performance quality after approximately 90 minutes, with error rates increasing and creative output decreasing.

The practical implication: 90-minute focused blocks align with your brain’s natural capacity for sustained high-performance work. Going longer often means diminishing returns; going shorter may not allow sufficient time to reach full cognitive engagement.

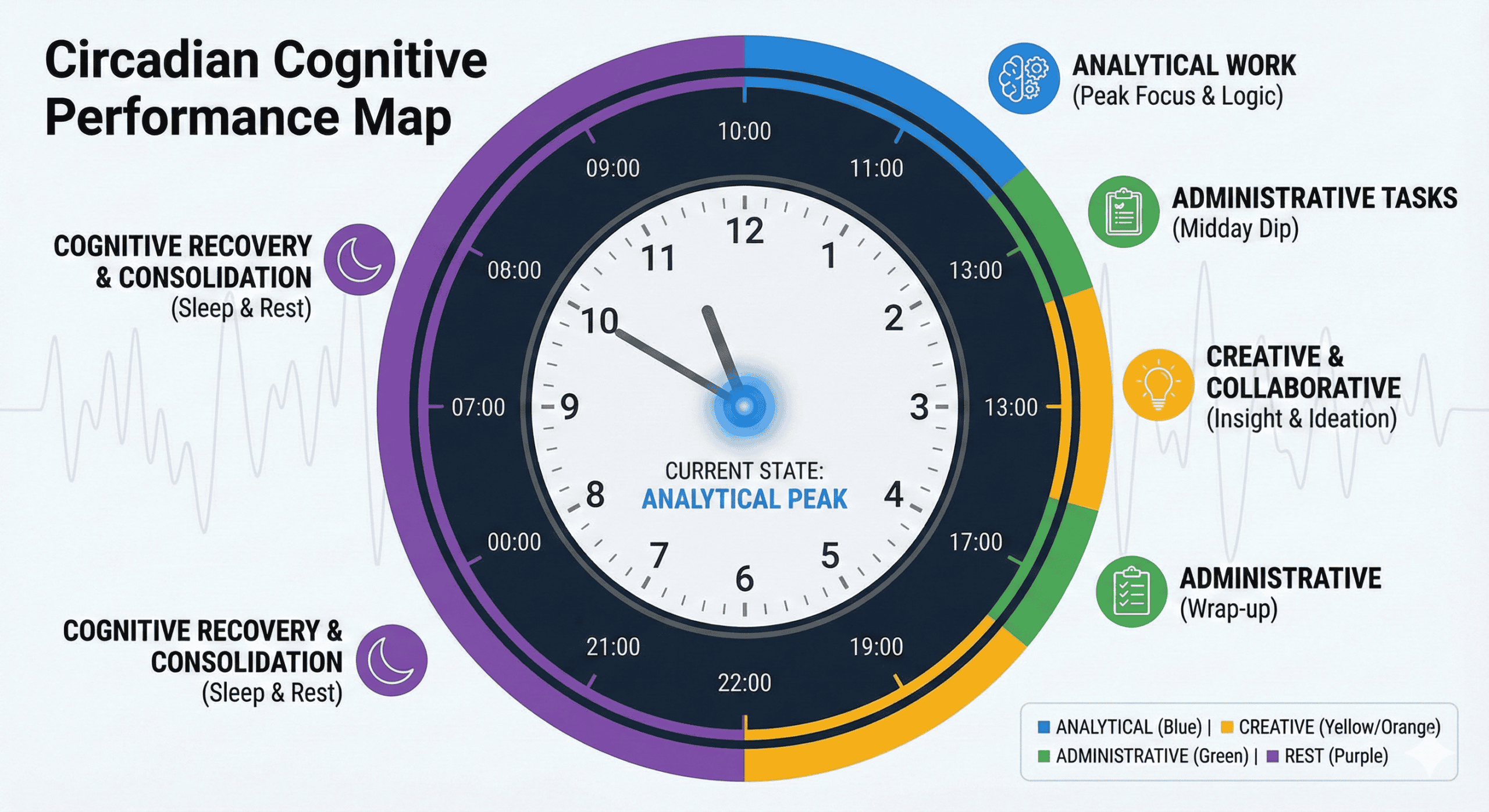

Circadian Rhythms: Timing Your Blocks

Beyond ultradian rhythms, your body follows 24-hour circadian rhythms that create predictable peaks and valleys in cognitive performance. Different cognitive functions peak at different times of day, and aligning your work blocks with these patterns can dramatically enhance productivity.

Research on circadian performance variations reveals several consistent patterns:

- Morning Peak (2-4 hours after waking): Analytical reasoning peaks. Best for complex problem-solving, strategic thinking, and learning new material.

- Mid-Morning to Early Afternoon: Sustained attention remains strong. Best for detailed analytical work, coding, and editing.

- Afternoon Dip (1-3 PM): Alertness decreases. Best for administrative tasks, routine work, meetings, and email.

- Late Afternoon Recovery (3-6 PM): Second wind of energy. Best for creative brainstorming and collaboration.

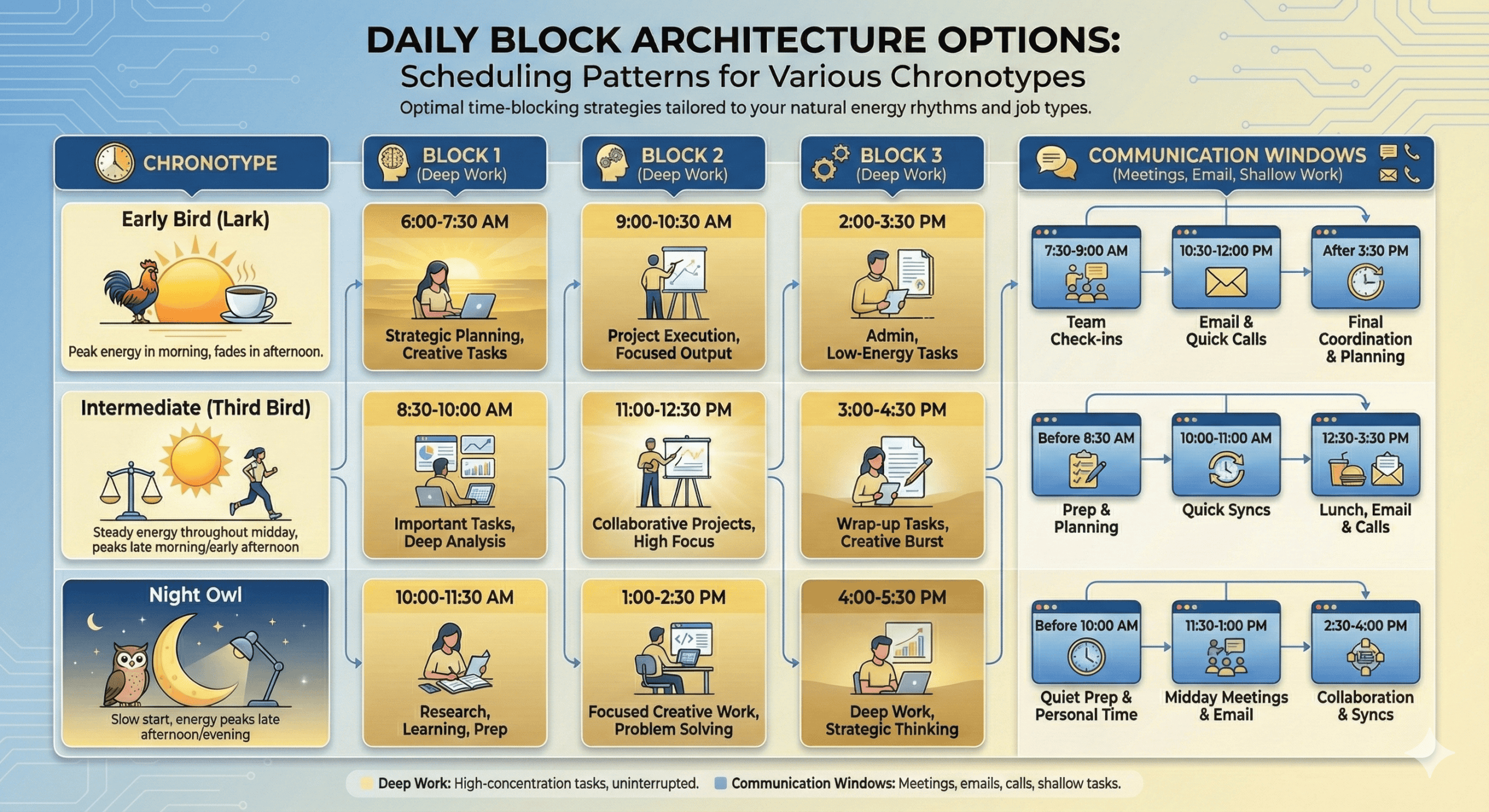

Chronotype Considerations

Individual differences in chronotype—whether you’re naturally a “morning lark” or “night owl”—significantly affect optimal scheduling. Research on chronotype and performance demonstrates that people perform better on cognitive tasks when those tasks are scheduled during their circadian peaks.

Research supports the value of chronotype alignment: studies show that students who study during their chronotype-matched hours outperform those who study at mismatched times, even when total study time is equivalent.

Flow blocks should be 60-120 minutes (optimal: 90 minutes) to align with ultradian rhythms, and scheduled during your circadian peak for the type of work you’re doing. Morning blocks for most analytical work, with flexibility based on your individual chronotype. Working with your biology amplifies results; working against it wastes effort.

Calendar Architecture for Flow System Design

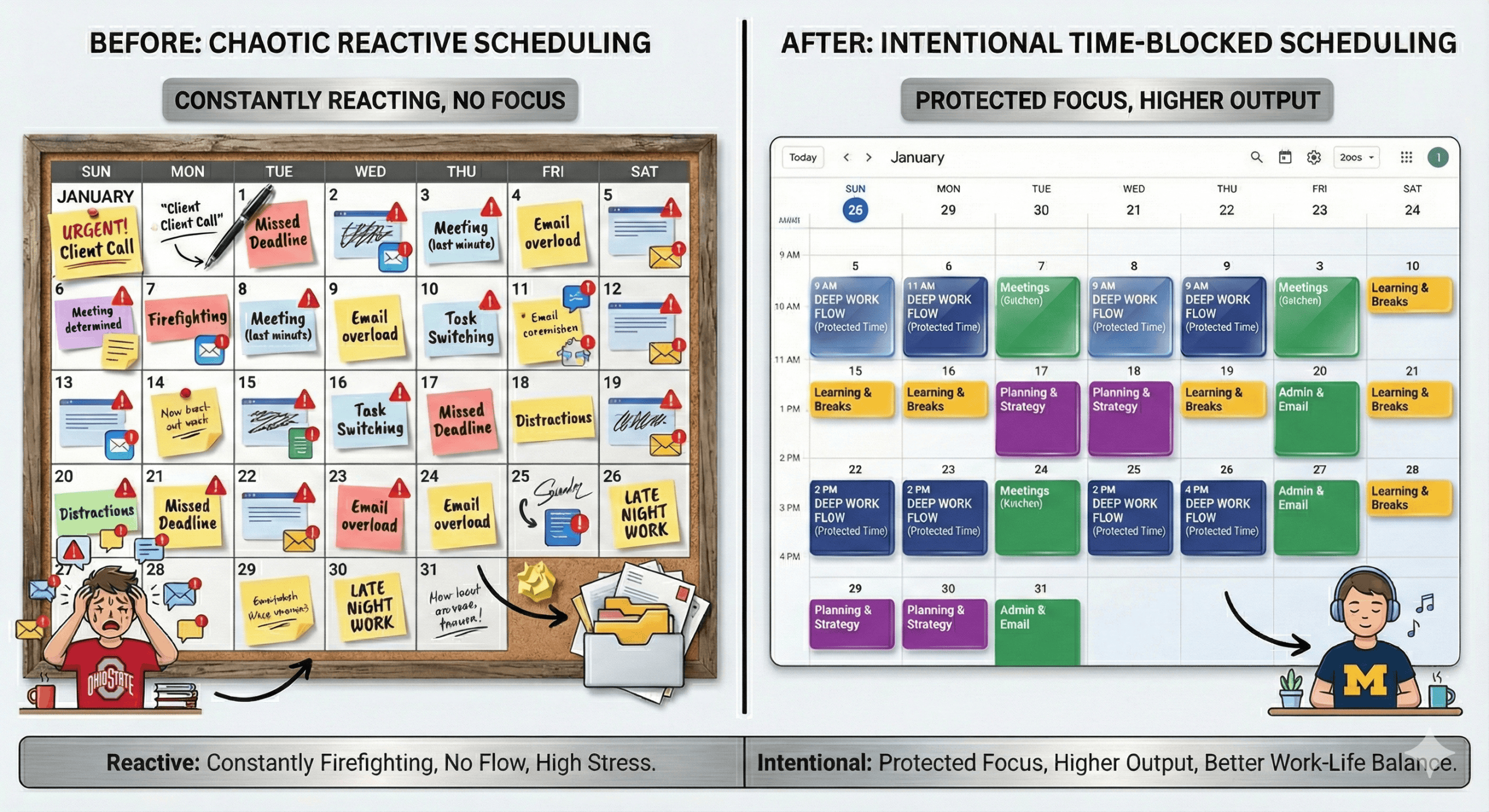

The Foundation: Time Blocking Methodology

Time blocking is the practice of scheduling specific activities into specific time slots on your calendar—treating every hour as a resource to be allocated intentionally rather than a void to be filled reactively.

Research on planning and time management demonstrates that people who schedule specific times for important activities are significantly more likely to complete them than those who merely intend to complete them “sometime.” This reflects the power of implementation intentions—the explicit linking of behavior to situational cues.

For flow blocks, time blocking serves multiple functions:

- Commitment device: Scheduled blocks are harder to sacrifice than unscheduled intentions.

- Visibility: Blocked time shows as “busy” to scheduling tools and colleagues.

- Planning foundation: Knowing when focus time occurs enables better scheduling of other activities.

- Psychological priming: Approaching a scheduled block triggers preparation mode.

The Three-Block Minimum

Research on deep work productivity suggests that most knowledge workers need a minimum of three 90-minute focus blocks per day to accomplish meaningful progress on important work. This totals 4.5 hours of focused work—which, when truly protected, produces more output than 8+ hours of fragmented attention.

Buffer Zones and Transition Time

Effective calendar architecture includes transition time between activities. Research on scheduling demonstrates that back-to-back scheduling without buffers increases stress, reduces performance, and leads to chronic running late.

For flow blocks specifically, buffer time serves critical functions:

- Pre-block buffer (10-15m): Time for your flow routine that triggers focus state.

- Post-block buffer (10-15m): Time for capturing notes, processing insights, and decompressing.

- Between-block buffer (20-30m): Recovery time that enables the next block to be productive.

Calendar Defense Strategies

Scheduling flow blocks is necessary but insufficient. You must also defend them from encroachment.

The Weekly Planning Ritual

Elite performers don’t just block time—they review and adjust their calendar architecture weekly. Research on planning suggests that consistent planning behavior is one of the strongest predictors of goal achievement.

Calendar architecture isn’t about rigidity—it’s about intentionality. By designing your calendar around protected focus blocks rather than filling gaps with them, you ensure that your highest-value work gets your highest-quality attention. Schedule flow blocks first, then build everything else around them.

The Four Types of Flow Blocks Classification

Not all focused work is the same. Effective calendar architecture recognizes that writing a complex proposal requires different cognitive conditions than learning a new skill or reviewing weekly metrics.

Purpose: Producing new work product—writing, coding, designing, building.

- Max protection (Phone out of room).

- No meetings before/after.

- Clear output goal required.

Purpose: Processing, analyzing, and sense-making of complex info.

- Data prepared in advance.

- Clear analytical question.

- Note-taking system ready.

Purpose: Acquiring new knowledge, skills, or certifications.

- Shorter duration (spaced repetition).

- Materials accessible instantly.

- Test understanding at end.

Purpose: Connecting ideas, planning, and sense-making.

- Moderate protection ok.

- Leverages “diffuse” thinking mode.

- Weekly reviews / Retro.

Sequencing Multiple Block Types

When scheduling multiple flow blocks in a single day, sequence matters. Energy naturally descends through the day; your work demands should descend with it.

Different types of focus work have different optimal conditions. Match block types to times of day, sequence strategically, and protect higher-demand blocks more rigorously. This differentiation allows for nuanced calendar architecture that maximizes total cognitive output.

Meeting Management and Communication Batching Defense

The primary threat to flow blocks isn’t personal willpower failures—it’s meetings and communication demands. Effective flow block systems must include strategies for managing these competing pressures.

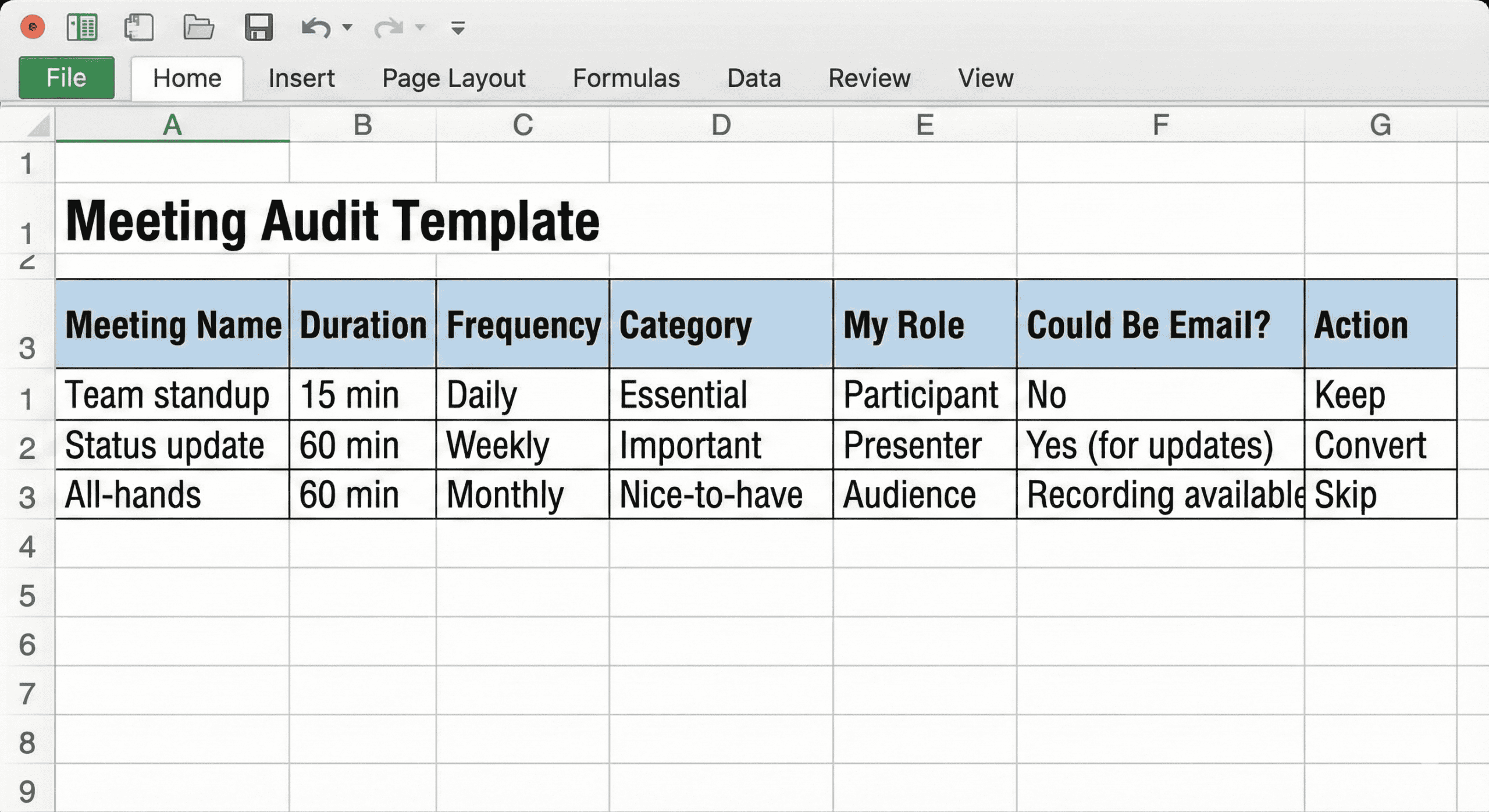

The Meeting Audit

Before implementing new meeting strategies, understand your current reality.

- Review: Check your calendar for the past 4 weeks.

- Count: Total meeting hours.

- Categorize: Essential / Important / Nice-to-have / Unclear purpose.

- Calculate: What percentage of meetings actually required your presence?

- Identify patterns: Which days are most meeting-heavy? Which times?

Research on meetings suggests that the average professional spends 23 hours per week in meetings, and executives report that more than 50% of meeting time is unproductive. Even modest improvements in meeting load can free significant time for focused work.

Meeting-Free Zones

One of the most effective strategies for protecting flow blocks is establishing meeting-free zones—times when meetings are simply not scheduled.

- Meeting-Free Mornings: No meetings before noon (or 11 AM). This protects the circadian analytical peak for deep work.

- Meeting-Free Days: One or more days per week with no scheduled meetings. Many organizations implement “No Meeting Wednesday” or similar policies.

- Meeting Windows: Meetings only scheduled during specific windows (e.g., 2-5 PM). Focus blocks fill remaining time.

Research on time-restricted scheduling shows that constraining when meetings can occur leads to more efficient meeting practices (shorter meetings, better preparation) without reducing necessary collaboration.

Implementing Meeting-Free Zones:

- Propose, don’t mandate: Frame as an experiment. “I’m trying meeting-free mornings for 30 days to see if it improves my output. Can we schedule our meetings for afternoons during this period?”

- Offer alternatives: Make it easy for people to work with you. “I’m available 2-5 PM on these days—which works for you?”

- Demonstrate results: Track and share productivity improvements. Evidence supports continued practice.

- Negotiate exceptions: Some meetings will need to occur during protected times. Evaluate case-by-case, but make exceptions feel like exceptions.

Meeting Batching

Research on task batching demonstrates that grouping similar activities together reduces the switching costs associated with transitions. This applies to meetings: scheduling meetings consecutively (rather than scattered) minimizes the total time lost to meeting-related transitions.

- Meeting Days vs. Focus Days: Designate certain days primarily for meetings, others primarily for focus work. Example: Meetings Tuesday/Thursday, Focus Monday/Wednesday/Friday.

- Meeting Blocks: If full meeting days aren’t feasible, create meeting blocks within days. Example: All meetings scheduled 2-5 PM, mornings protected for focus.

- Meeting Types Batched Together: Schedule similar meetings consecutively. All 1:1s on Monday afternoon. All project meetings on Thursday.

Communication Batching

Email, Slack, and other communication channels pose a subtler but equally significant threat to flow blocks. Research on email behavior shows that constant email checking is associated with higher stress and lower productivity, while batched checking improves both.

(30 min)

(30 min)

(30 min)

- Set Windows: Check email/Slack only during designated windows (e.g., 9 AM, 12 PM, 4 PM). Three times daily is typically sufficient for most roles.

- Communicate Expectations: Let colleagues know your communication rhythm. “I check email three times daily. For urgent matters, call me.”

- Use Status Indicators: Set Slack/Teams status to indicate focus mode. “Focused Work – Will respond by [time]”

- Batch Similar Communications: Process all email at once, then close. Don’t leave email open in the background.

Research supports the effectiveness of batched communication: studies show that restricting email checking to 3 times daily reduces stress and improves well-being compared to unlimited checking.

Handling Urgency Concerns

A common objection to communication batching is “but what about urgent things?” Research suggests that true urgency is rare, and most “urgent” matters can wait 2-4 hours without consequence.

For legitimate urgency needs:

- Define “urgent” explicitly with your team (system down, safety issue, time-sensitive client need).

- Establish an alternative channel for true emergencies (phone call, specific Slack channel).

- Trust the system—if something is truly urgent, people will find a way to reach you.

Scripts for Protecting Time

Sometimes protection requires direct communication. Here are evidence-based scripts for common situations:

Meetings and communication aren’t inherently bad—they’re essential for collaboration. But unmanaged, they’ll consume all available time. Proactive meeting management (audits, batching, meeting-free zones) and communication batching (designated windows, status indicators) protect the blocks where deep work happens.

Defending Your Blocks Against Interruption Countermeasures

Even well-scheduled blocks face constant pressure from interruptions. Defense strategies fall into two categories: prevention (stopping interruptions before they occur) and response (handling interruptions effectively when they happen).

Prevention: Environmental Defenses Shields Up

Your focus setup and environment provides the first line of defense.

- Closed door: If you have an office, close it.

- Headphones: Universal signal for “do not disturb.”

- Location change: Library, empty room, or home.

- Visual barriers: Face away from traffic.

- Phone relocation: Another room entirely.

- Notification elimination: All off.

- Browser blocking: Block social/news/email.

- App closure: Close (don’t minimize) comms apps.

- Availability signaling: “Do Not Disturb” signs.

- Explicit comms: Tell team you are entering flow.

- Cultural norms: Model focus time protection.

Prevention: Scheduling Defenses Strategic Timing

Strategic scheduling choices reduce interruption pressure.

- Early Morning: Before 8-9 AM (Low traffic).

- Lunch Overlap: 11 AM – 1 PM (Reduced meetings).

- End-of-Day: 4-5:30 PM (Fewer invites).

- Double-booking: Show as “Busy”.

- Buffer events: 15m protective buffers.

- Decoy meetings: “Meeting with self” vs “Focus”.

- Remote work: Use WFH days for deep blocks.

- Location variation: Learn where interruptions happen.

- Peak alignment: Block when interrupters are busy.

Response: When Interruptions Happen Protocols

Despite prevention, some interruptions will occur. How you respond determines whether they derail your block or merely pause it.

Managing Expectations

Long-term interruption reduction requires expectation management with colleagues, managers, and clients.

Defense is multilayered: environmental controls prevent many interruptions, scheduling strategies reduce exposure, and response protocols minimize damage from unavoidable disruptions. The goal isn’t zero interruptions—it’s minimizing their frequency and impact on your protected focus time.

The 30-Day Flow Blocks Protocol

This protocol provides a systematic, day-by-day approach to implementing flow blocks in your schedule. Follow it sequentially for optimal results.

- Review: Your calendar for the past 4 weeks.

- Count: Total meeting hours, total focus hours, interruption frequency.

- Identify: Which days/times are most meeting-heavy? Most available?

- Document: What’s your current productive output per week?

- Time investment: 30-45 minutes.

- Assess your natural energy patterns (morning lark, night owl, intermediate).

- Track energy levels hourly for one day (simple 1-10 ratings).

- Identify your personal peak performance window.

- Note: When do you naturally feel most focused?

- Design your ideal daily block structure.

- Choose: How many blocks (minimum 2, ideal 3)?

- Choose: What duration (60-90-120 minutes)?

- Choose: What times align with your chronotype?

- Create a visual template of your ideal day.

- Block your designed flow blocks for the next two weeks.

- Use clear labels: “FOCUSED WORK – No Meetings”.

- Set blocks to show as “Busy”.

- Schedule 15-minute buffer before and after each block.

- Add block preparation reminders.

- Prepare your focus setup.

- Identify phone parking location.

- Test notification silencing.

- Prepare website blockers.

- Create physical signals (headphones, sign, closed door).

- Draft your communication rhythm (when you’ll check email/Slack).

- Inform key stakeholders of your new schedule.

- Set up out-of-office or status messages for focus periods.

- Establish emergency contact protocol.

- Review all preparation completed.

- Identify any gaps or concerns.

- Confirm first week of blocks is scheduled.

- Mentally commit to the protocol.

- Execute your first scheduled flow block.

- Perform your pre-flow routine.

- Work for the full scheduled duration.

- Rate: Block quality (1-10), interruptions (count), output satisfaction (1-10).

- Execute scheduled flow blocks daily.

- Track: Start time (on time?), actual duration, interruption count, quality rating.

- Note: What worked? What challenged the block?

- Adjust: Make minor environmental adjustments as needed.

- Calculate: How many scheduled blocks were completed as planned?

- Review: What were the primary block disruptors?

- Compare: Output quality/quantity vs. previous baseline.

- Plan: What adjustments will improve Week 3?

- Review upcoming 2-week meeting load.

- Categorize each meeting (Essential/Important/Nice-to-have).

- Identify at least 2 meetings to decline, shorten, or convert to email.

- Implement changes.

- Implement strict communication windows.

- Check email/Slack only at designated times (start with 3 times daily).

- Track compliance: Did you stick to windows?

- Note: What urgency concerns arose? How were they resolved?

- Assign different block types to different times.

- Morning: Creation blocks.

- Mid-day: Analysis blocks.

- Afternoon: Learning or integration blocks.

- Track: Does type-timing alignment improve quality?

- Review interruption log from past two weeks.

- Identify top 3 interruption sources.

- Design specific countermeasures for each.

- Implement countermeasures.

- Assess meeting management impact.

- Evaluate communication batching effectiveness.

- Compare block quality across different types and times.

- Document learnings and adjustments.

- Execute all system components simultaneously.

- Maintain block protection with all defenses active.

- Continue tracking all metrics.

- Note patterns and optimize in real-time.

- Calculate total blocks completed vs. scheduled over 30 days.

- Compare output quantity and quality to Day 1 baseline.

- Assess subjective satisfaction with the system.

- Identify: What’s working well? What needs adjustment?

- Document your finalized flow block system.

- Record: Block timing, duration, types, meeting policy, communication protocol.

- Create maintenance checklist for ongoing operation.

- Schedule 30-day check-in for system review.

- Celebrate completion!

Success Metrics for the Protocol

- Block completion rate: 80%+ of scheduled blocks executed as planned.

- Meeting reduction: 15-25% reduction in total meeting hours.

- Output improvement: Meaningful increase in deep work output (self-assessed).

- Blocks feel natural and sustainable.

- Colleagues respect protected time.

- Quality of work noticeably improved.

- Stress and overwhelm reduced.

- Completion rate below 60% by Week 2: System may be too ambitious—reduce block count.

- No output improvement by Week 3: Block protection may be inadequate—strengthen defenses.

- High stress by Week 4: System may not fit role requirements—adjust approach.

Advanced 30-Day Protocol for Elite Performance

This advanced protocol is for those who have completed the foundational protocol and maintained consistent flow block practice for at least 60 days. It introduces sophisticated strategies for maximizing focus time effectiveness.

- Completed the foundational 30-day protocol.

- Maintained 80%+ block completion rate for 30+ additional days.

- A stable flow block schedule that feels sustainable.

- Tracking data showing improved output during blocks.

- Specific goals for further optimization.

- Install time-tracking software if not already in use.

- Set up detailed productivity metrics for flow blocks.

- Establish baseline: output per block hour, quality ratings, energy patterns.

- Review block quality ratings from previous months.

- Identify: Which blocks are consistently highest quality? Lowest?

- Analyze: What variables correlate with quality? (Time of day, block type, preceding activity).

- Document patterns.

- Track detailed energy levels every 30 minutes for 2 days.

- Identify ultradian rhythm patterns in your specific biology.

- Map optimal times for each block type based on energy data.

- Identify energy drain sources and recovery needs.

- Synthesize all performance data.

- Identify highest-leverage optimization opportunities.

- Plan Week 2 schedule refinements.

- Document insights.

- Redesign block schedule to align with your observed ultradian rhythms.

- Schedule blocks to start during energy upswings.

- Schedule breaks during natural energy dips.

- Test optimized schedule.

- Experiment with different block durations.

- Test: Are you more effective with 60, 75, 90, or 120-minute blocks?

- Track quality and sustainability at each duration.

- Identify optimal duration for each block type.

- Analyze time lost in transitions between blocks.

- Optimize pre-block routines for speed and effectiveness.

- Create “quick start” protocols for different block types.

- Test reduced-friction transitions.

- Assess schedule optimization impact.

- Finalize optimal block timing and duration.

- Document optimized schedule parameters.

- Prepare for Week 3 advanced techniques.

- Experiment with “mega-blocks”—two consecutive blocks with a brief (10-minute) break.

- Test 180-minute extended sessions for complex projects.

- Track quality degradation (if any) in extended blocks.

- Identify appropriate use cases for extended blocks.

- Experiment with theme days: days dedicated to specific types of work.

- Example: Deep Creation Monday, Analysis Tuesday, Meeting Wednesday.

- Track effectiveness compared to mixed-type days.

- Identify optimal theme structure for your work.

- Integrate energy management practices with block scheduling.

- Test: Pre-block exercise, nutrition timing, caffeine timing.

- Track impact on block quality.

- Evaluate advanced technique effectiveness.

- Identify which techniques to incorporate permanently.

- Document optimal protocols.

- Plan Week 4 integration.

- Operate complete optimized system.

- All advanced techniques active.

- Continue tracking all metrics.

- Fine-tune in real-time.

- Deliberately test system under challenging conditions.

- High meeting load day: Can you maintain minimum viable blocks?

- High-pressure deadline: Does system hold up?

- Identify failure modes and create contingencies.

- Assess: Is this system sustainable long-term?

- Identify any components causing strain.

- Adjust for sustainability vs. maximum performance.

- Document sustainable operating parameters.

- Create comprehensive documentation of optimized system.

- Include: schedule, protocols, contingencies, maintenance routines.

- Make documentation accessible and actionable.

- Final metrics review.

- Compare to foundational protocol baseline.

- Document total improvement achieved.

- Plan ongoing optimization approach.

- Schedule quarterly system reviews.

- Review block quality data weekly.

- Adjust schedule based on upcoming demands.

- Maintain block journal for pattern recognition.

- Comprehensive performance review.

- Test new optimization techniques.

- Adjust for seasonal/project phase changes.

- Full system audit.

- Major schedule restructuring if needed.

- Review and update documentation.

- Set next quarter optimization goals.

Domain-Specific Flow Strategies

Different roles and contexts require different approaches to flow blocks. Here are detailed strategies for common situations.

- Physical Separation: Create a dedicated workspace. When you enter, work starts. When you leave, work ends.

- Structured Day Design: Without office cues, design explicitly: Morning focus, Midday meetings (batch video calls), Afternoon focus/integration, Hard stop time.

- Video Meeting Batching: Batch ruthlessly to protect remaining time.

- Camera-Off Focus Time: Establish “online but silent” periods for shared focus energy without interruption.

- Accountability Structures: Use time tracking logs and partner check-ins to replace peer observation.

- EA Partnership: Train your EA to protect focus time with explicit criteria.

- Meeting-Free Mornings: No meetings before 10 AM. Protects strategic thinking.

- Strategic Days: Monthly/Quarterly off-site days for deep strategy.

- Decision Block: Use specific “Office Hours” for drop-ins instead of an open door policy.

- Delegation: Protect cognitive bandwidth for true executive work.

- Minimum Viable Blocks: Even 45-minute blocks matter. Start with what’s realistic.

- Strategic Timing: Use naturally quiet times (early AM, lunch overlap).

- Communication SLAs: “I respond within 4 hours” allows focus without abandoning responsiveness.

- Asynchronous Shifts: Replace live meetings with detailed emails/recordings.

- Team Coverage: Rotate “on-call” status so others can focus.

- Creation vs. Production: Separate generative work (mood-sensitive) from production work. Protect creation most.

- Mood-Responsive: Capture inspiration when it strikes. Pivot to production if creative blocks feel dead.

- Extended Sessions: Schedule 2-3 hour blocks for major projects where flow builds slowly.

- Input/Output Separation: Schedule research (input) separately from creation (output).

- Class Integration: Build blocks around fixed class times. Use gaps strategically.

- Standardization: Same time, same place. Habits reduce decision load.

- Subject Rotation: Interleave subjects across blocks for better retention.

- Library Default: Use built-in environmental protection. Home requires too much willpower.

- Study Groups: Structure them: silent co-working + discussion intervals.

Your role and context determine which flow block strategies will work best. Executive calendars require different tactics than student schedules. Remote work faces different challenges than open offices. Adapt the core principles to your specific situation rather than forcing a generic solution.

Measuring Flow Block Effectiveness

What gets measured gets managed. Systematic tracking enables continuous improvement of your flow block system.

Review Protocols

- How many blocks were scheduled vs completed?

- What was the average quality rating?

- What interrupted blocks? Prevention plan?

- Which times produced best blocks?

- What adjustments for next week?

- Review all weekly data points.

- Calculate monthly aggregates.

- Compare to previous months/baseline.

- Identify trends (improving/declining).

- Make structural adjustments if needed.

Continuous Improvement Cycle

Use data to drive improvement:

Frequently Asked Questions

Implement minimum viable blocks: even one 45-minute protected block daily provides meaningful deep work time. Communicate explicit response times: “I respond within 2-4 hours during business hours” allows for blocks without abandoning responsiveness. For roles with genuine constant-availability requirements (emergency services, critical support), adapt: shorter blocks, strategic timing, team coverage rotation.

Second, demonstrate results: when your protected time produces exceptional work, make the connection visible. Third, offer compromise: perhaps you can protect morning blocks but be flexible afternoons. Fourth, manage up: help your boss understand the productivity math—fragmented attention costs more than protected time delivers.

Flow blocks should NOT contain email processing, routine administrative tasks, meetings, or any work that doesn’t require sustained concentration. Save these for non-block time. The test: “Does this task require deep focus to do well?” If yes, it belongs in a flow block.

Guideline: Keep 80%+ of blocks intact. Accept occasional disruption. If you’re compromising more than 20% of blocks, something systemic needs addressing—either block protection is inadequate, scheduling is unrealistic, or role fit needs evaluation.

Better approach: protect a block before lunch and a block after lunch, with a genuine 30-60 minute break between. If you want more block time, add an early morning block rather than sacrificing lunch recovery.

Also check: Are you well-rested? Research shows sleep deprivation significantly impairs sustained attention. Is the work appropriately challenging? Too easy leads to boredom; too hard leads to frustration—both break focus. Are you properly fueled? Dehydration and blood sugar crashes impair concentration.

Third, offer alternatives: “I’m not available during that time, but I am available [specific times]—which works for you?” Fourth, enlist allies: if your manager or team lead supports your system, their backing helps establish norms.

However, some flexibility serves certain roles. Consistent core blocks (e.g., always morning) with flexible secondary blocks can balance structure with adaptability. The minimum: have at least one block at a consistent time to anchor your schedule.

When legitimately interrupted: capture your current state (30 seconds), handle the priority, then return with a brief re-entry routine. Don’t let one interruption cascade—protect the remainder of your block.

During crunch periods: maintain minimum viable blocks (at least 2 daily), reduce meeting load even further (decline all non-essential meetings), and be even more aggressive about communication batching. Protect your cognitive capacity for the work that matters most.

Signs you’ve scheduled too many blocks: consistently failing to complete them, cognitive exhaustion, important non-block work accumulating, relationships suffering from over-protection. Find the sustainable rhythm that works for your role—usually 3-4 blocks totaling 3-5 hours.

Protecting What Matters Most

The difference between ordinary output and exceptional achievement isn’t talent—it’s structural.

The math is stark: the average knowledge worker spends 2.1 hours per day on focused work. Elite performers spend 4-5 hours. That 2-3 hour difference, compounded over years, represents the gap between ordinary output and exceptional achievement.

Flow blocks aren’t a productivity hack—they’re a recognition of how high-quality cognitive work actually gets done. Your brain requires uninterrupted time to engage complex problems fully. Task-switching taxes cognitive resources. Attention residue degrades performance even after you’ve returned to your primary task. These aren’t flaws to overcome through willpower—they’re features of how brains work.

The solution is structural: design your time to give your brain what it needs. Schedule protected blocks aligned with your ultradian and circadian rhythms. Build calendar architecture that defends these blocks. Batch meetings and communication into windows. Create environmental and social defenses against interruption.

The implementation is straightforward but not easy. You’ll face cultural pressure to be constantly available. Colleagues will test your boundaries. Some meetings will conflict with protected time. The temptation to “just check email quickly” will persist.

Resist. The compound benefit of protected focus time—exceptional work, career advancement, reduced stress, greater satisfaction—far exceeds the cost of defending it.

Command Center

Access related modules to refine your system: